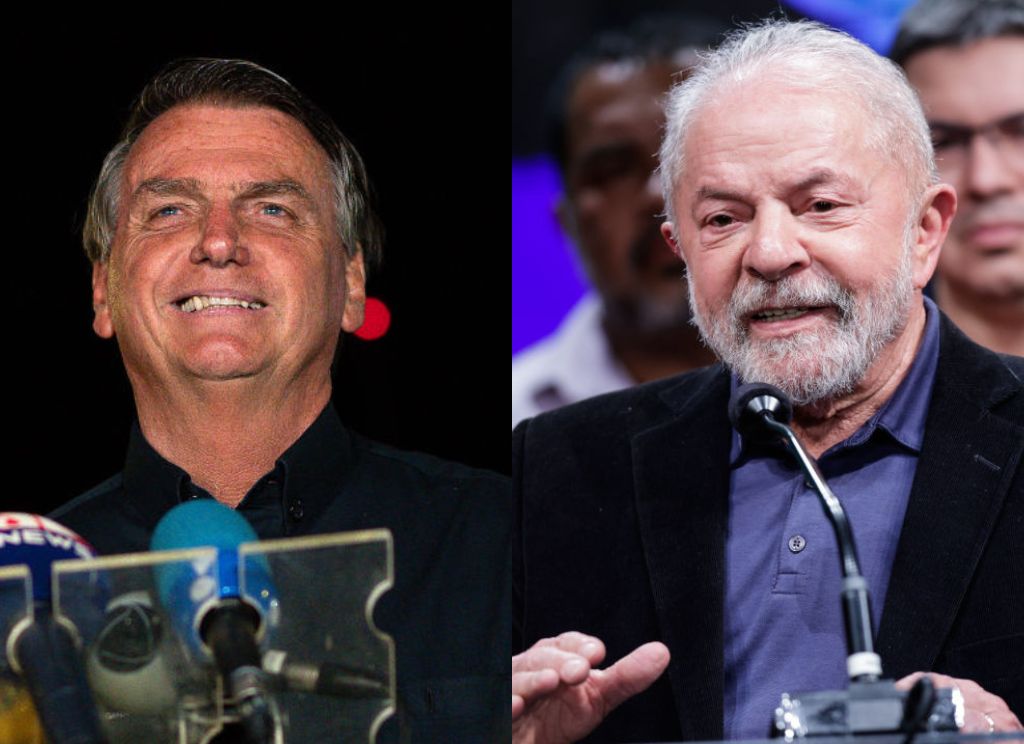

Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and President Jair Bolsonaro are headed to a runoff election on October 30 after a first round that took many by surprise. Despite polls consistently showing Lula ahead by around 10 percentage points—and even the possibility that he would win outright in the first round with over 50% of the vote—the final result was much closer: Lula finished ahead with 48.4% of the vote, while Bolsonaro reached 43.2%. The incumbent led the vote count for several hours, accumulating large-margin wins in the South, Center-West and Southeast regions. Northeastern voters pulled Lula ahead in the last hours of the vote-counting. The former president also won the count in the northern Amazon region. But bolsonarismo showed its strength in Brazil, winning majorities in the House and the Senate as well as key governorships.

AQ asked observers to share their reaction.

Brian Winter, editor-in-chief at Americas Quarterly

The result was a surprise, but let’s take a deep breath and look at the big picture. Lula is still the favorite in this race after finishing ahead by 6 million votes. He is likely to get an endorsement from the third place finisher Simone Tebet, who had 4% of the vote, and take most of the votes for Ciro Gomes, who had 3%. Lula will have no choice but to move toward the center now, and that’s good news for Brazil’s economy and financial markets.

That said, this will be a very competitive second round, one that will put Brazil’s democracy under stress and probably leave lasting scars. These two men, and their supporters, genuinely hate each other. With a margin this close, the odds again increase that Bolsonaro will declare fraud if he loses on Oct. 30 and that some of his supporters may take to the streets to try to overturn the result.

Some people believed Bolsonaro would lose big, and he would go down in Brazilian history as a kind of aberration. That’s over now. Bolsonaro and bolsonarismo are here to stay, even if Lula does win the runoff. With yesterday’s results, and the wave of pro-Bolsonaro figures elected to Congress and governorships, the president can credibly claim to be the leader of a conservative movement with energy and staying power. Brazil’s Evangelical Christian community is growing, society overall is more conservative than it was 20 years ago, and I think we are still trying to understand the implications of this going forward.

The big loser was the polls. I repeatedly warned during this campaign that we should be skeptical, but they were even more inaccurate than I feared. I don’t know if the problem is methodology, or respondents not being truthful, or just conservative voters being undercounted in many countries all over the world. But I’m done—I won’t be paying attention to any polls for the next four weeks. The only numbers that matter now are the ones that will be counted on election day.

Laura Karpuska, economist and professor at Insper

The first round of elections has shown the consolidation of the right in Brazil, solidifying a strongly ideological bolsonarismo movement in the country. The 2023 Senate will have a majority of seats aligned with Bolsonaro, and the 2023 Chamber of Deputies, although more balanced, will also have more seats occupied by deputies from Bolsonaro’s PL party and the União Brasil party that is aligned with the current president. There will be significant turnover in Congress, with former Bolsonaro cabinet members winning strong popular support with significant shares of the vote in their respective states.

Former President Lula is still likely to be elected president in the runoff. But it won’t be an easy road. He needs to speak to financial markets—where participants, in informal surveys, indicate a preference for keeping Bolsonaro in the presidency—and to undecided voters about what road, which kind of policies he plans to pursue. Looking into the past to imagine the future, as his campaign jingle suggests, won’t be enough. Lula will need to be clear about who will be in his economic team and about the political alliances that could lead him to capture supporters of Simone Tebet (4.16% of the first-round vote) and Ciro Gomes (3%).

The main takeaways from the first-round elections in Brazil is that the right became more focused on ideology than the economy, and it is more organized than the left. Market participants meanwhile seem to be playing down the risk of having a stronger ideological right in the country. The cooptation of Brazil’s budget in the form of secret allocations to deputies (orçamento secreto) and the changes made to the nation’s budgetary plans to support increased spending during the election season—such as providing vouchers to cab and truck drivers and extending cash transfers without a technical analysis—apparently were not enough to frighten those concerned with fiscal accounts in Brazil.

Oliver Stuenkel, international relations professor at Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV)

While Lula won the first round by a smaller margin than expected, he remains the favorite in the runoff. Since democratization, all candidates who won the first round have proceeded to win the second round, and Bolsonaro would have to pull off a historic comeback to win reelection—not impossible, but still unlikely. Still, in order to secure victory in the second round, Lula can be expected to intensify his efforts to reach out to centrists. If he wins, the Workers Party (PT), and in particular the left wing of the party, will have far less influence than during his government from 2003-2010.

Lula would also face formidable resistance in Congress, making major progress on several fronts (such as the fight against deforestation) less likely. The Bolsonaro campaign will attempt to use the momentum of yesterday’s stronger than expected showing to catch up, arguing that a second presidential mandate—this time with broader support in Congress—would allow him to implement policies without the constraints he faced during the first four years. The bolsonarista tsunami in the Senate and Congress will make the Lula campaign project itself as the last barrier against the emergence of an empowered and increasingly authoritarian Bolsonaro.

The next four weeks are likely to be shaped by intensifying polarization and high risk of increased political violence. Given that polls failed to adequately predict the result and are unlikely to adjust their models in time, analysts will largely be in the dark about potential shifts in support between Bolsonaro and Lula, as well as in several runoffs for governor. From a more long-term perspective, the October 2 results show that, even if Lula wins, bolsonarismo is here to stay for years to come and will have a significant influence on Brazilian politics, in areas such as health, education and the environment.

Amy Erica Smith, associate professor of political science and liberal arts and sciences dean’s professor at Iowa State University

The strong narrative coming out of last night’s election is that Bolsonaro did substantially better and Lula somewhat worse than polls had predicted. Although a five-point spread with Lula coming in just a bit shy of an outright majority had looked quite likely months ago, the fact that the race tightened substantially in recent days contributes to a narrative of Lula having lost ground. Lula is now in precisely the second-round scenario he had hoped to avoid. It also bears mentioning that this is the scenario many experts had pointed to as being riskiest for Brazilian democracy: a narrow race in which Bolsonaro can credibly claim that something was off with the polls.

In the coming days, the major task for polling and survey experts is going to be to figure out why the final results were tighter than most recent polls had predicted. In broad strokes, I see three possibilities. The first is that polls for some reason did a poor job of reaching the kinds of people who are Bolsonaro supporters in terms of demographics. From what I know, this seems unlikely, but it’s definitely something to examine. The second possibility is that Bolsonaro supporters were for some reason less likely to respond to polls. Although some supporters of both Bolsonaro and Lula may have been afraid or embarrassed to admit their choices to pollsters, Bolsonaro’s insistence that polls were biased against him may have inadvertently made his supporters especially reluctant to answer polls. The final possibility is that Bolsonaro benefited from a lot of last-minute switching and deciding. Here, Protestant churches might have played an outsized role, as my own research shows that there can often be big swings in evangelical churches in the final days before an election.